Kuulo Kutsar

E-CDC risk status: endemic

(last edited: date 22.04.2024, data as of end 2023)

History and current situation

The first cases of tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) in Estonia were identified in 1949. Today, Estonia is a TBE- endemic country. A TBE-endemic area in Estonia is defined as an area with circulation of the TBEV between ticks and vertebrate hosts as determined by detection of the TBEV or the demonstration of autochthonous infections in humans or animals within the last 20 years.

Euro-Asian genotypes of TBEV – the Western or European (TBEV-EU), Siberian (TBEV-Sib), and Far-Eastern (TBEV-FE) subtypes are co-circulating in Estonia. Vectors of TBEV, the tick species Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes persulcatus, are distributed throughout the country.

The high-risk season for infection coincides with the period of biological activity of ticks and lasts for 7 months from April to November, peaking in June to August.

Most TBE cases are diagnosed in persons ≥60 years of age and the incidence among the rural population is 1.8 times higher than among the urban population.

Overview of TBE in Estonia

| Table 1: TBE in Estonia | |

|---|---|

| Viral subtypes, distribution | Co-circulation of European (TBEV-EU), Far-Eastern (TBEV-FE), and Siberian (TBEV-Sib) subtypes |

| Reservoir animals | Rodents, ruminants, game |

| Infected tick species (%) | 2011: I. persulcatus 8%, I. ricinus on mainland 0.6% – 0.8% and Saaremaa 3.0%. 2013: Estonia: I. persulcatus 4.23%, I. ricinus 0.42%. 2018: Tallinn 0.44% – 2.7% 2023: Estonia 1.1% – 8.3%: Valga county 6.1% and Viljandi county 8.3%. |

| Dairy product transmission | Documented but rare |

| Mandatory TBE reporting | Reporting: neurologists, infectious disease specialist Case definition Clinical criteria: a person with symptoms of the central nervous system (meningitis, meningoencephalitis, encephalomyelitis, encephaloradiculitis) Laboratory criteria for case confirmation: At least 1 of the following: – TBE-specific IgM and IgG antibodies in blood – TBE-specific IgM antibodies in CSF – Seroconversion of 4-fold increase of TBE-specific antibodies in paired serum samples – Detection of TBE viral nucleic acid in a clinical specimen – Isolation of TBEV from clinical specimens. Probable case: detection of TBE-specific IgM antibodies in a unique serum sample Epidemiological criteria Exposure to a common source (unpasteurized dairy product). Case classification: – Possible case: not applicable – Probable case: a person meeting the clinical criteria and the laboratory criteria for a probable case OR a person meeting the clinical criteria and with an epidemiological link – Confirmed case: a person meeting the clinical and laboratory criteria for case confirmation |

| Other TBE surveillance | Laboratory and epidemiological surveillance |

| Special clinical features | Biphasic disease: meningitis, meningoencephalitis, or meningoencephalomyelitis. Risk groups: people who often spend time outdoors (in nature) |

| Available vaccines | ENCEPUR CHILDREN, ENCEPUR ADULTS, TICOVAC CHILDREN, TICOVAC ADULTS (Table 2) |

| Vaccination recommendations and reimbursement | Vaccination recommendations 1998. No reimbursement; self-paid |

| Vaccine uptake by age group/risk group/general population | Vaccine uptake by general population (vaccinated and revaccinated): 2018 – 3.1%; 2019 – 3.7%; 2020 – 3.4%; 2021 – 2.6%, 2022 – 4,1%, 2023 – 5,8%. (Table 2) |

| Name, address/website of TBE National Reference Center | Health Board, Tallinn Paldiski St 81; https://www.terviseamet.ee |

| Table 2: TBE vaccination by age in Estonia, 2022 |

|---|

| Age | Vaccination (3 doses) | Revaccination (dose 4 or more) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 - 14 | 6513 | 6544 |

| 15 - 17 | 418 | 1261 |

| Adults | 14475 | 25800 |

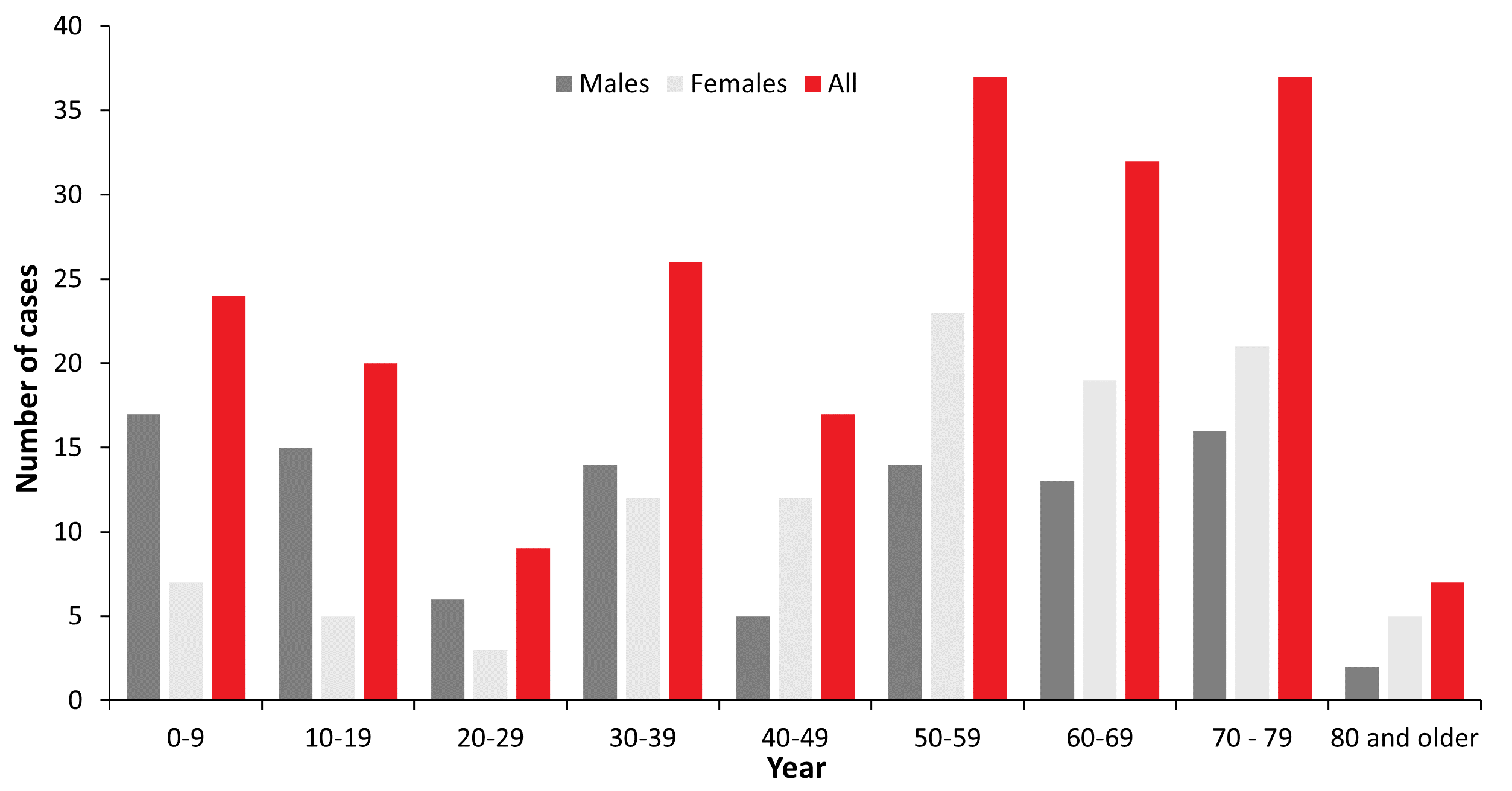

| Age (years) | Males | Females | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 - 9 | 17 | 7 | 24 |

| 10 - 19 | 15 | 5 | 20 |

| 20 - 29 | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| 30 - 39 | 14 | 12 | 26 |

| 40 - 49 | 5 | 12 | 17 |

| 50 - 59 | 14 | 23 | 37 |

| 60 - 69 | 13 | 19 | 32 |

| 70 - 79 | 16 | 21 | 37 |

| 80 and older | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Total | 102 | 107 | 209 |

TBE seasonality: case numbers, Estonia 2023

January – 1, February – 1, March – 0, April – 0 , May – 3 , June – 20 , July – 19, August – 49, September – 45, October – 56, November – 11, December – 4 cases

TBE total cases 209 and incidence 15.6 per 100 000 population in Estonia 2023

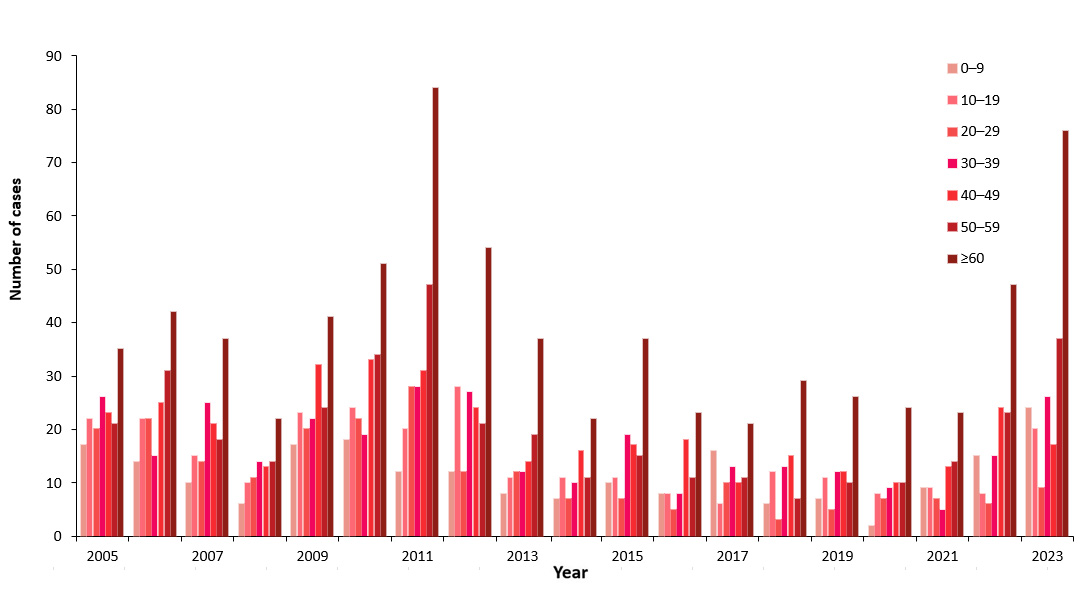

| Year | 0-9 | 10-19 | 20-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | 60≥ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 17 | 22 | 20 | 26 | 23 | 21 | 35 |

| 2006 | 14 | 22 | 22 | 15 | 25 | 31 | 42 |

| 2007 | 10 | 15 | 14 | 25 | 21 | 18 | 37 |

| 2008 | 6 | 10 | 11 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 22 |

| 2009 | 17 | 23 | 20 | 22 | 32 | 24 | 41 |

| 2010 | 18 | 24 | 22 | 19 | 33 | 34 | 51 |

| 2011 | 12 | 20 | 28 | 28 | 31 | 47 | 84 |

| 2012 | 12 | 28 | 12 | 27 | 24 | 21 | 54 |

| 2013 | 8 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 19 | 37 |

| 2014 | 7 | 11 | 7 | 10 | 16 | 11 | 22 |

| 2015 | 10 | 11 | 7 | 19 | 17 | 15 | 37 |

| 2016 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 18 | 11 | 23 |

| 2017 | 16 | 6 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 11 | 21 |

| 2018 | 6 | 12 | 3 | 13 | 15 | 7 | 29 |

| 2019 | 7 | 11 | 5 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 26 |

| 2020 | 2 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 24 |

| 2021 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 13 | 14 | 23 |

| 2022 | 15 | 8 | 6 | 15 | 24 | 23 | 47 |

| 2023 | 24 | 20 | 9 | 26 | 17 | 37 | 76 |

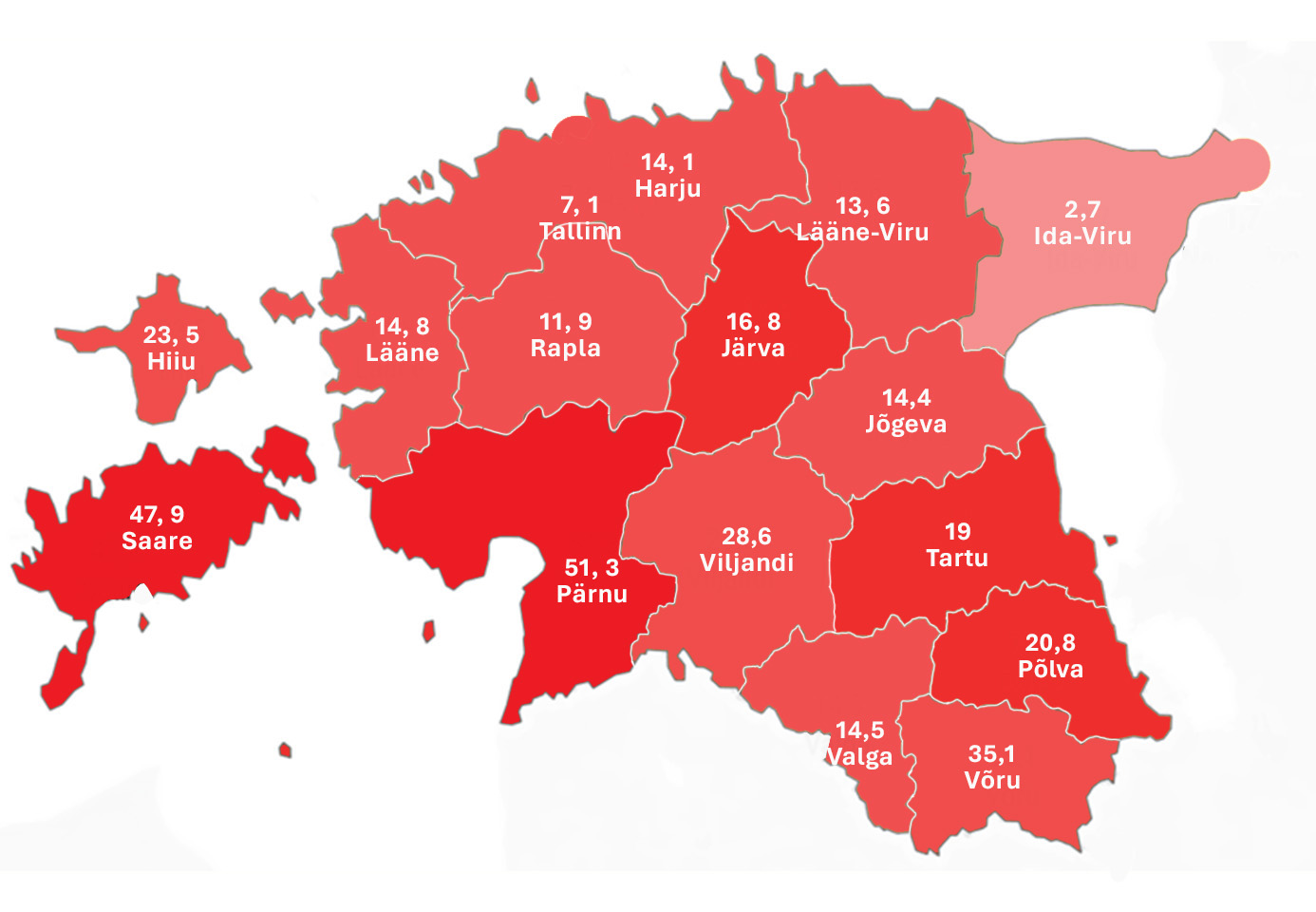

| Counties | Cases |

|---|---|

| Tallinn (capital) | 31 |

| Harjumaa | 25 |

| Hiiumaa | 2 |

| Ida-Virumaa | 3 |

| Järvamaa | 5 |

| Jõgevamaa | 4 |

| Läänemaa | 3 |

| Lääne-Virumaa | 8 |

| Pärnumaa | 45 |

| Põlvamaa | 5 |

| Raplamaa | 4 |

| Saaremaa | 15 |

| Tartumaa | 30 |

| Valgamaa | 4 |

| Viljandimaa | 13 |

| Võrumaa | 12 |

| Total | 209 |

Contact

Kuulo Kutsar

kkutsar@hotmail.com

Author

Citation

Kutsar K. TBE in Estonia. Chapter 13. In: Dobler G, Erber W, Bröker M, Chitimia-Dobler L, Schmitt HJ, eds. The TBE Book. 7th ed. Singapore: Global Health Press; 2024. doi:10.33442/26613980_13-10-7

References

- Health Board of Estonia. [Nakkushaiguste esinemine ja immunoprofülaktika]. 2022. Accessed 9 April, 2024.

- https://www.terviseamet.ee/sites/default/files/Nakkushaigused/Haigestumine/epid_ulevaade_2022_0.pdfKatargina O, Russakova S, Geller J et al. Detection and characterization of tick-borne encephalitis virus in Baltic countries and Eastern Poland. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e61375

- Geller J, Vikentjeva M. [Ticks as disease carriers in the green areas of Tallinn and the surrounding area]. 2020. Accessed 30 March, 2024. https://www.tai.ee/sites/default/files/2021-03/159852954118_Pealinna%20rohealade%20puugid%20ja%20puugihaigused.pdf

- Vikentjeva M, Geller J. Linnapuugid 2023 – puukide levimus ja puugihaiguste oht Eesti linnade avalikel haljasaladel. Tervise Arengu Instituut. 2023. Accessed 30 March 2024. https://tai.ee/sites/default/files/2023-09/Linnapuugid_2023.pdf