Katarzyna Pancer

E-CDC risk status: endemic

(last edited in May 2025, update for 2024: 803 reported cases)

History and current situation

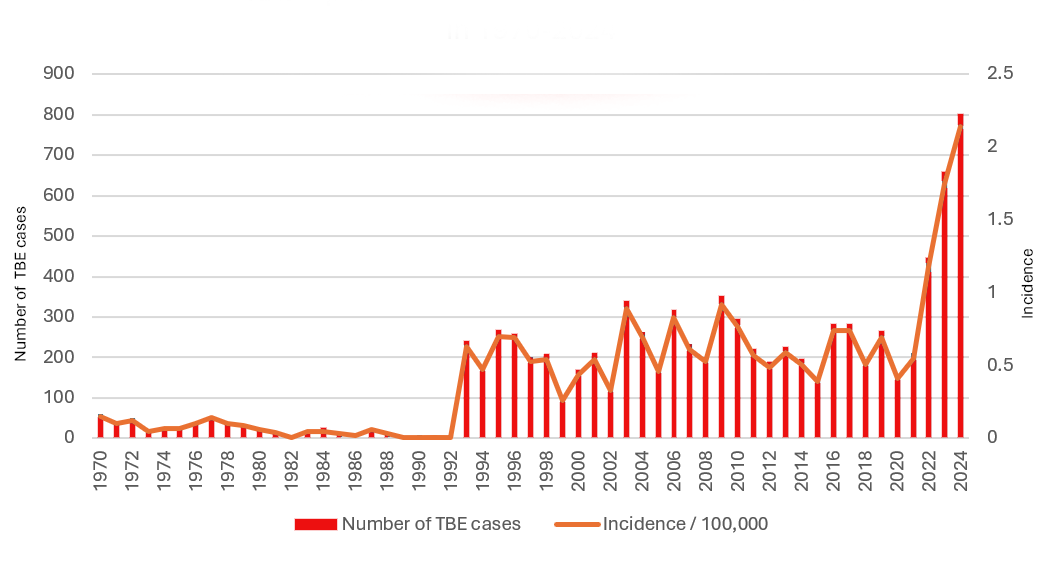

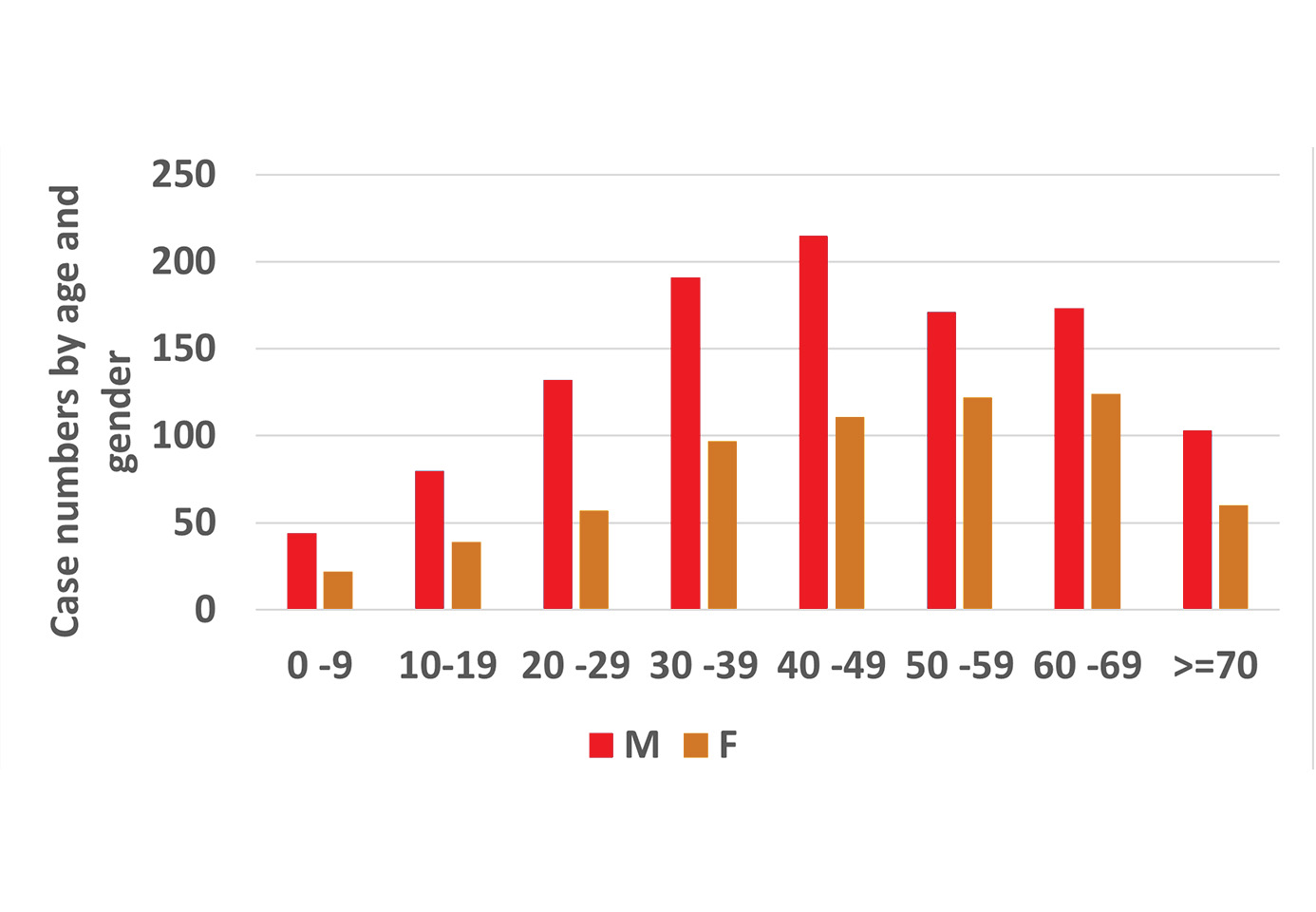

The history of tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) in Poland started in 1948, when clinical symptoms of TBE were described by Demiaszkiewicz.7 Disease reporting has been mandatory since 1970. In the years between 1970-1992, a total of 576 TBE cases were reported; the annual number varied from 4 (1991) to 60 (1970), and the incidence in that period ranged from 0.01/100,000 population to 0.2/100,000 inhabitants, respectively. In 1993, however, the number of reported TBE cases increased rapidly, probably because of the first introduction of commercial tests serologically to confirm the diagnosis of TBE by ELISA, which rapidly replaced the older HI assay (Fig.1).2,3,15 As in other European countries, TBE cases occur mainly in men aged 30-60 y. (Fig.2).

This trend continued through the 1990s into the beginning of the 21st century. The number of reported TBE cases ranged from 149 in 2015 to 315 cases in 2009. In total, 4,690 cases of TBE were reported in Poland between 2000 and 2019. The respective incidence varied from 0.33 to 0.92/100,000. Possibly, a 3–4-year cycle was identified based on the reported numbers of TBE cases, with peaks observed in 2003, 2006, and 2009, but in the next years the cycle varied and peaks were observed in 2016, 2017 and 2019 (Fig.1).2,15

During the early 2020s strong effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were observed. In contrast to neighboring Germany and Sweden15 there was a decrease in reported case numbers in Poland. However, data from another independent surveillance system, the Nationwide General Hospital Morbidity Study (NGHMS), which collects data about hospitalizations for TBEV and other viral neuro-infections, indicated a large increase of clinical TBE detections at the same time. An analysis of data collected from different databases indicated that the sensitivity of the Polish epidemiological surveillance system for TBE still needs to improve and that the suboptimal use of laboratory diagnostics for identification of the etiological agent in patients with presumed viral CNS-infection is probably the main reason for the underestimation of TBE in Poland.16 The same conclusion was drawn based on the results of a project that retrospectively verified diagnoses in cases of viral neuro-infections.21 It is necessary to expand the scope of diagnostics of neuro-infections to include tests for TBEV, particularly outside known endemic areas.

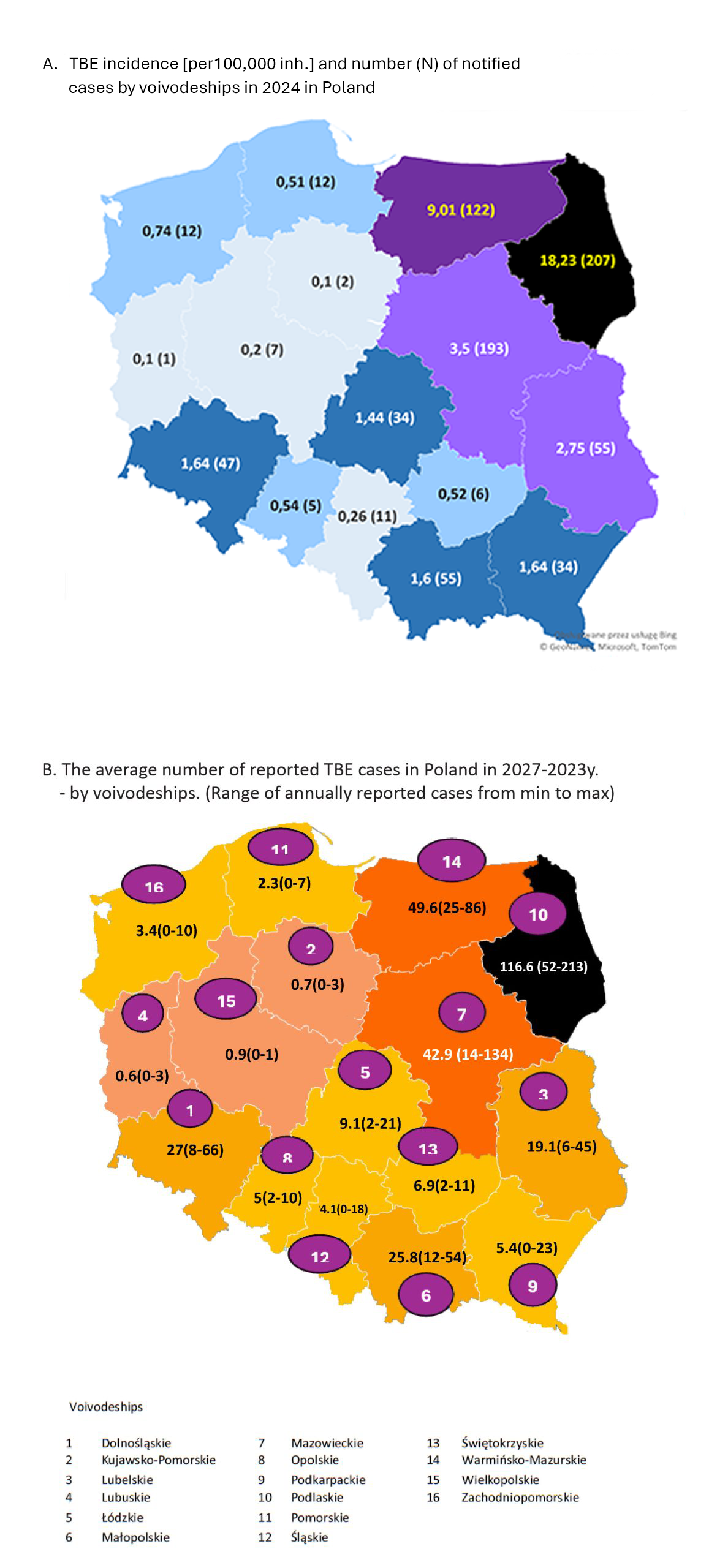

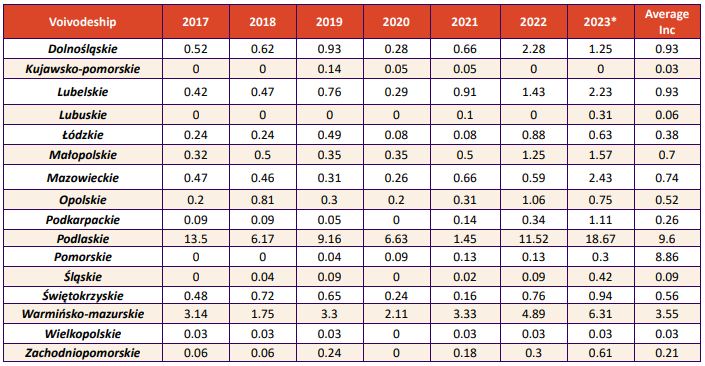

Over the last 4 years (2020-2023), a constant and significant increase in the number of TBE cases has been observed in Poland, reaching up to 663 cases with an incidence of 1.76/100,000 population in 2023.2 Moreover changes in the geographic distribution of TBE cases were observed in this period: while in previous decades each year more than 60% of TBE cases were detected in just 2 provinces in northeastern Poland (Podlaskie, >45% reported TBE cases; Warmińsko-Mazurskie, 15%-25% of reported cases), in the last 4 years, the predominance of reported cases in the Podlasie Province was reduced to 32%, whereas the proportion of TBE cases in Mazowieckie voivodeship increased from 10% to 15.8%. The ratio of TBE cases in Warmińsko-Mazurskie was stable (15%). The lowest incidence was observed in Lubuskie voivodeship: usually there were no reported TBE cases, with exception of 2023 (3 cases) (Fig.3).2

Moreover, more cases were diagnosed in autumn and early winter in the recent years and the percentage of TBE cases reported between October and December increased in comparison to other seasons (2018: 50%; 2022: 42%). One possible explanation for this phenomenon is climate change, with higher temperatures than in previous periods, longer heat waves, periods of drought and violent atmospheric phenomena occurring with varying intensity in Poland.

Vaccination against TBE in Poland started in the 1970s. Vaccines using the TBEV-European strain have been available since 1993 and are recommended for persons staying in endemic TBE areas, specifically forest workers, soldiers, hunters, border guards, firefighters, farmers, tourists and campers of any age as of one year of age. There is no reimbursement.3 Vaccine uptake was low before 2019 (0.05-0.12%). Since 2019, the number of vaccinations has increased twice, especially among children and young adults <19 years of age. Today, the total number of adults and children vaccinated each year are similar – in 2022 – 41,728 vs 41,292.1

Overview of TBE in Poland

| Table 1: TBE in Poland1,3-6,8-21 | |

|---|---|

| Viral subtypes isolated | European subtype (TBEV-EU)9,11,14 |

| Reservoir animals | Mainly small mammals like: Apodemus sylvaticus, Apodemus flavicollis, Rinaceus roumanicus, Myodes glareolus, Microtus agrestis, Sciurus vulgaris, Sorex araneus, Talpa europaea8 |

| Infected tick species (%) | Varied depending on regions and vector:4,13,17,19,20 · from 0 to 1.6% in I.ricinus, mainly found in North-Eastern and Eastern Poland. · from 0.99 to 12.5% in D.reticulatus (Central Poland -7.6%; Eastern – up to 10.8%; North-Eastern – 0.99-12.5%). |

| Diary product transmission | Sporadic cases and limited outbreaks5,6,10,18 |

| Case definition used by authorities | Based on ECDC15 |

| Completeness of case detection and reporting | Comparison of surveillance data and other data from hospitalization and National Health Fund databases indicated strong underreporting of TBE in 202016 Retrospective verification of clinical recognition – undetected cases of TBE were found in 13.9% of examined patients21 |

| Type of reporting | Mandatory reporting of all cases with neuroinfection. Passive surveillance; obligatory reporting of TBE detection by clinicians as well as positive results of laboratory diagnostics by labs15 |

| Other TBE-surveillance | No available data |

| Special clinical features | 70-80% Biphasic Clinical manifestation: fever 95.3%; headache 95%, muscle pain 43%, dizziness 6.3%, vomiting 42%, neurological disorders 11%, meningeal symptoms 70%15,21 |

| Licensed vaccines | Commercially available products are: FSME-IMMUN (FSME-IMMUN 0,25-ml Junior, FSME-IMMUN 0,5-ml) and Encepur (Encepur K for children >1 year old; Encepur Adults >12. year old) |

| Vaccination recommendations | Risk groups related to occupation or habits; no reimbursement3 Vaccination for TBE is recommended for persons employed in forest exploitation; military; firefighters and border guards; farmers; people engaging in particularly frequent physical activity outdoors. |

| Vaccine uptake | Vaccine uptake differs by region; highest usually in the highly affected regions with an incidence >5/100,000; in 2021, 0.5% of the general population in Podlaskie voivodeship was vaccinated in comparison to 0.18% in the general population of Poland1 |

| National Reference center for TBE | Since 2004 Poland has had no National Reference Center for TBE |

| Additional relevant information | Two fatal cases due to organs transplanted from donors with TBE viremia were described.12 The cases may indicate a potential risk of TBEV transmission by transplantation and transfusion |

Figure 1: TBE case numbers and incidence in Poland (1970-2023)2 Update for 2024: 803 reported cases

Figure 2: Age and gender distribution of TBE in Poland, 2019-20222

Figure 3: Average annual incidence of TBE and cumulative case numbers in Poland, 2017-2023, by region (voivodeship)

Addendum: Table with incidence of TBE per 100,000 inhabitants in voivodeships in Poland in 2017-2023*

*temporary data

Acknowledgments

Data on reported TBE cases come from the database maintained by the Department of Infectious Diseases Epidemiology and Surveillance financed by the National Health Programme (NPZ) 2021-2025 (6/8/85195/NPZ/2021/1094/827).

Contact

Katarzyna Pancer

kpancer@pzh.gov.pl

Author

Citation

Pancer K. TBE in Poland. Chapter 13. In: Dobler G, Erber W, Bröker M, Chitimia-Dobler L, Schmitt HJ, eds. The TBE Book. 7th ed. Singapore: Global Health Press; 2024. doi:10.33442/26613980_13-25-7

References

- National Institute of Public Health NIH – NRI, GIS. Vaccinations in Poland; 2000-2022. Accessed April 8, 2024. http://wwwold.pzh.gov.pl/oldpage/epimeld/index_p.html

- National Institute of Public Health NIH – NRI, GIS. Infectious diseases and poisonings in Poland; 1990-2023. Accessed April 8, 2024. http://wwwold.pzh.gov.pl/oldpage/epimeld/index_p.html

- Act on Prevention and combating infections and infectious diseases in humans [Art. 20. Recommended protective vaccinations when performing specific professional activities] Journal of Laws. 2020 Pos. 567

- Biernat B, Karbowiak G, Werszko J, Stańczak J. Prevalence of tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) RNA in Dermacentor reticulatus ticks from natural and urban environment, Poland. Exp Appl Acarol. 2014;64(4):543-551. doi:10.1007/s10493-014-9836-5

- Buczek AM, Buczek W, Buczek A, Wysokińska-Miszczuk J. Food-Borne Transmission of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus-Spread, Consequences, and Prophylaxis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1812. Published 2022 Feb 5. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031812

- Cisak E, Wójcik-Fatla A, Zając V, Sroka J, Buczek A, Dutkiewicz J. Prevalence of tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) in samples of raw milk taken randomly from cows, goats and sheep in eastern Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2010;17(2):283-286.

- Demiaszkiewicz W. [Spring-summer tick encephalitis in the Bialowieza Forest]. Pol Tyg Lek (Wars). 1952;7(24):799-801.

- Gliński Z, Kostro K, Grzegorczyk K. [Rodents as potential carriers of pathogenic microorganisms]. Zycie Weterynaryjne. 2017; 92(11): 799-804.

- Katargina O, Russakova S, Geller J, et al. Detection and characterization of tick-borne encephalitis virus in Baltic countries and eastern Poland. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e61374. Published 2013 May 1. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061374

- Monika Emilia Król, Bartłomiej Borawski, Anna Nowicka-Ciełuszecka, Jadwiga Tarasiuk, Joanna Zajkowska. Outbreak of alimentary tick-borne encephalitis in Podlaskie voivodeship, Poland. Przegl Epidemiol. 2019;73(2):239-248. doi:10.32394/pe.73.01

- Kunze M, Banović P, Bogovič P, et al. Recommendations to Improve Tick-Borne Encephalitis Surveillance and Vaccine Uptake in Europe. Microorganisms. 2022;10(7):1283. Published 2022 Jun 24. doi:10.3390/microorganisms10071283

- Lipowski D, Popiel M, Perlejewski K, et al. A Cluster of Fatal Tick-borne Encephalitis Virus Infection in Organ Transplant Setting. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(6):896-901. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix040

- Mierzejewska EJ, Pawełczyk A, Radkowski M, Welc-Falęciak R, Bajer A. Pathogens vectored by the tick, Dermacentor reticulatus, in endemic regions and zones of expansion in Poland. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:490. Published 2015 Sep 24. doi:10.1186/s13071-015-1099-4

- Moraga-Fernández A, Muñoz-Hernández C, Sánchez-Sánchez M, Fernández de Mera IG, de la Fuente J. Exploring the diversity of tick-borne pathogens: The case of bacteria (Anaplasma, Rickettsia, Coxiella and Borrelia) protozoa (Babesia and Theileria) and viruses (Orthonairovirus, tick-borne encephalitis virus and louping ill virus) in the European continent. Vet Microbiol. 2023;286:109892. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2023.109892

- Paradowska-Stankiewicz I., Zbrzezniak J. Tick-borne encephalitis in Poland and worldwide. Assessment of the epidemiological situation of TBE in Poland in 2015-2019 based on epidemiological surveillance data. NIPH NIH-NRI Report. 2021. Accessed April 8, 2024. https://www.pzh.gov.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/KleszczoweZapalenieMozgu-raport-PZH_2021.pdf

- Paradowska-Stankiewicz I, Pancer K, Poznańska A, et al. Tick-borne encephalitis epidemiology and surveillance in Poland, and comparison with selected European countries before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2008 to 2020. Euro Surveill. 2023;28(18):2200452. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2023.28.18.2200452

- Stefanoff P, Pfeffer M, Hellenbrand W, et al. Virus detection in questing ticks is not a sensitive indicator for risk assessment of tick-borne encephalitis in humans. Zoonoses Public Health. 2013;60(3):215-226. doi:10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01517.x

- Wójcik-Fatla A, Krzowska-Firych J, Czajka K, Nozdryn-Płotnicka J, Sroka J. The Consumption of Raw Goat Milk Resulted in TBE in Patients in Poland, 2022 “Case Report”. Pathogens. 2023;12(5):653. Published 2023 Apr 27. doi:10.3390/pathogens12050653

- Wójcik-Fatla A, Cisak E, Zając V, Zwoliński J, Dutkiewicz J. Prevalence of tick-borne encephalitis virus in Ixodes ricinus and Dermacentor reticulatus ticks collected from the Lublin region (eastern Poland). Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2011;2(1):16-19. doi:10.1016/j.ttbdis.2010.10.001

- Zając V, Wójcik-Fatla A, Sawczyn A, et al. Prevalence of infections and co-infections with 6 pathogens in Dermacentor reticulatus ticks collected in eastern Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2017;24(1):26-32. doi:10.5604/12321966.1233893

- Zajkowska J, Waluk E, Dunaj J, et al. Assessment of the potential effect of the implementation of serological testing tick-borne encephalitis on the detection of this disease on areas considered as non-endemic in Poland – preliminary report. Przegl Epidemiol. 2021;75(4):515-523. doi:10.32394/pe.75.48