Pavle Banović

E-CDC risk status: endemic

(last edited in May 2025, update for 2024: no data)

History and current situation

Tick-borne encephalitis virus (Orthoflavivirus encephalitis; TBEV) was reported in Serbia for the first time in 1972 when 2 TBEV strains were isolated from questing Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes persulcatus collected in the Pešter plateau (Western Serbia).1,2 Since then, there were no reports about TBEV in questing ticks until 2017, when Potkonjak et al. reported presence of TBEV-Eu in I. ricinus ticks collected at Fruška Gora Mountain (North Serbia) and suburban parts of Belgrade.3 Regardless of occasional TBEV findings in ticks from Serbia, there is still no evidence of active TBEV foci in any part of the country, as data from reservoir and sentinel animals are lacking.

Serosurveys conducted in the period of 1962-1969 via hemagglutination inhibition test found great variation in prevalence of TBEV-reactive antibodies in populations across Serbian regions, with the highest seroprevalence rate in the Sandžak-Raška region (52.6%), followed by Kosovo Autonomous Province (37.8%), Western Serbia (19.4%), Banat (8%) and Belgrade region (7.3%). Regions with lowest seroprevalence were Southeastern Serbia (3.6%) and Srem (1.1%). Nevertheless, these results should be interpreted with caution, since hemagglutination inhibition tests can’t distinguish TBEV-neutralizing antibodies from antibodies generated against West Nile virus (Orthoflavivirus nilense; WNV),4 that was most probably circulating within Yugoslavia in the same period.2

Clinicians in Serbia were facing an obstacle in TBE diagnosis until TBEV-neutralization assay was developed by Pasteur Institute Novi Sad in 2022.5 More precisely, due to antibody cross-reactivity, there is a high probability that cases of Tick-Borne Encephalitis (TBE) will be misdiagnosed as West Nile encephalitis if ELISA is the only assay used for indirect diagnostics in patients with viral inflammation of the central nervous system.6 In the same year (2022), a fatal case of imported TBE was described in South Serbia, where neutralization assay was used to confirm the suspected etiology in a patient returning from Switzerland.5

In a serosurvey comparing TBEV-exposure in tick-infested individuals from two Balkan cities (Novi Sad in Serbia and Skopje in North Macedonia), TBEV-neutralizing antibodies were found in one subject from Skopje (1/45; 2.22%) and in none of the enrolled persons from Novi Sad (0/51;0%).7 Nevertheless, a larger-scale study focused on tick-infested individuals from North Serbia revealed the presence of TBEV-neutralizing antibodies in three individuals (3/450; 0.66%).8

Overview of TBE in Serbia

| Table 1: TBE in Serbia | |

|---|---|

| Viral subtypes isolated | TBEV-Eu3 |

| Reservoir animals | N/A, no surveillance is established 9 |

| Infected tick species (%) | 0%,10 no surveillance is established 9 |

| Dairy product transmission | N/A |

| Case definition used by authorities | There is no nationally regulated TBE case definition. Clinical center of Serbia uses following case definition: Characteristic clinical picture with TBEV-reactive IgM and IgG in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid, done by ELISA with negative serological finding for West Nile-Virus, Herpes simplex virus 1, varicella zoster virus, B. burgdorferi, Leptospira sp. and Brucella sp.11 |

| Type of reporting | Mandatory |

| Other TBE-surveillance | Since January 2020, surveillance according to the EU Clinical Case Definition has been introduced in all hospitals in Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, as a part of Special Public Health Program. Program is based on software application for Case Definition detection in all departments for infectious diseases. |

| Special clinical features | N/A |

| Licensed vaccines | No TBE vaccine is licensed in Serbia |

| Vaccination recommendations | While no TBE-vaccine is licensed in the country, immunization is recommended for the population living in TBE endemic areas, as well as for professionals and recreational individuals entering TBEV hotspots12 |

| Vaccine uptake | No |

| National Reference center for TBE | National reference center for TBE: Institute of Virology, Vaccines and Sera “Torlak” Vojvode Stepe 458, Belgrade. Laboratory with TBEV-neutralization assay: Pasteur Institute Novi Sad, Hajduk Veljkova 1, Novi Sad. |

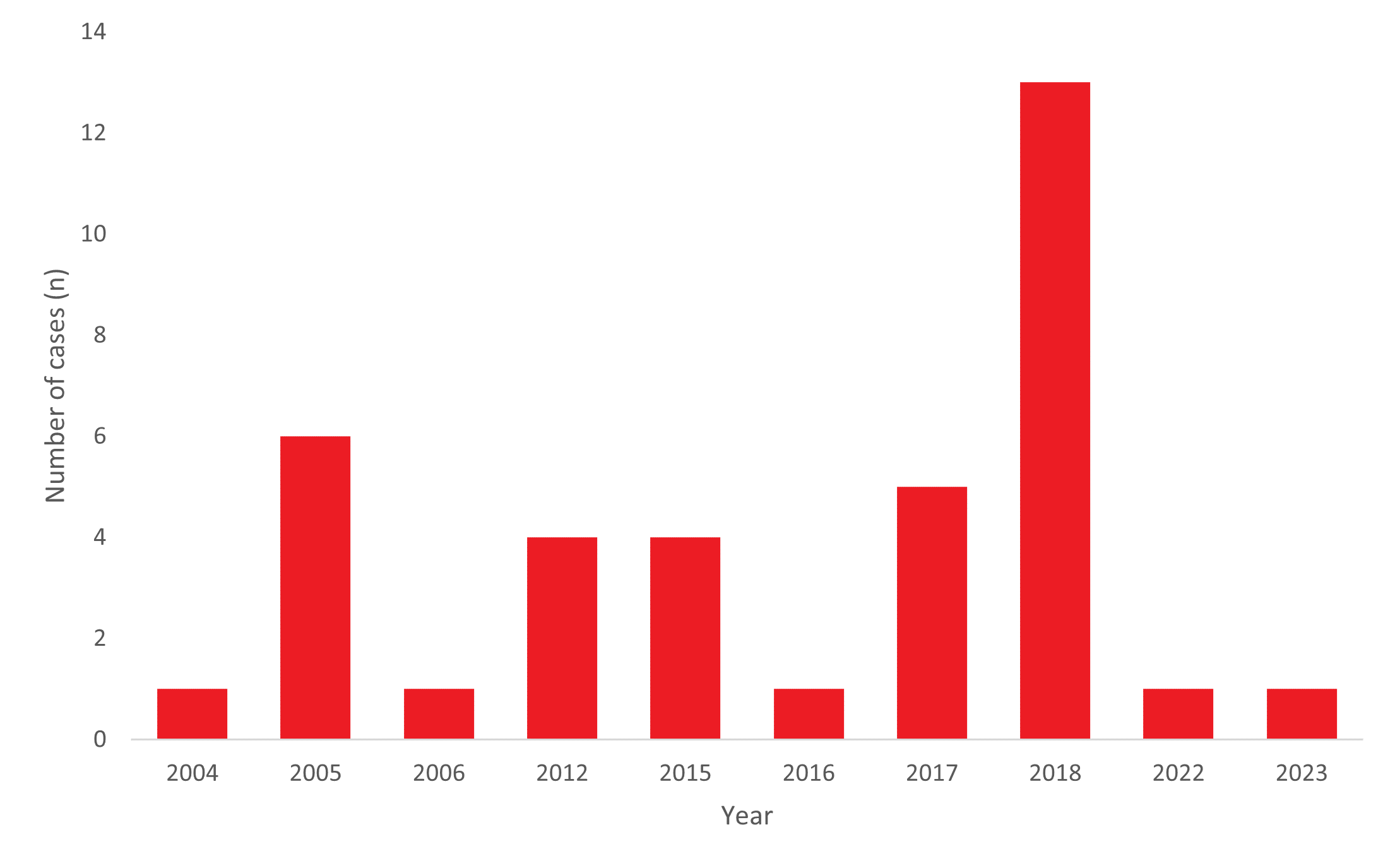

Figure 1: TBE cases 2004-2023. Update for 2024: No data

NOTE: The TBE case definition is different from the E-CDC definition, see Table 1 above

| Year | Number of Cases |

|---|---|

| 2004 | 1 |

| 2005 | 6 |

| 2006 | 1 |

| 2012 | 4 |

| 2015 | 4 |

| 2016 | 1 |

| 2017 | 5 |

| 2018 | 13 |

| 2022 | 1 |

| 2023 | 1 |

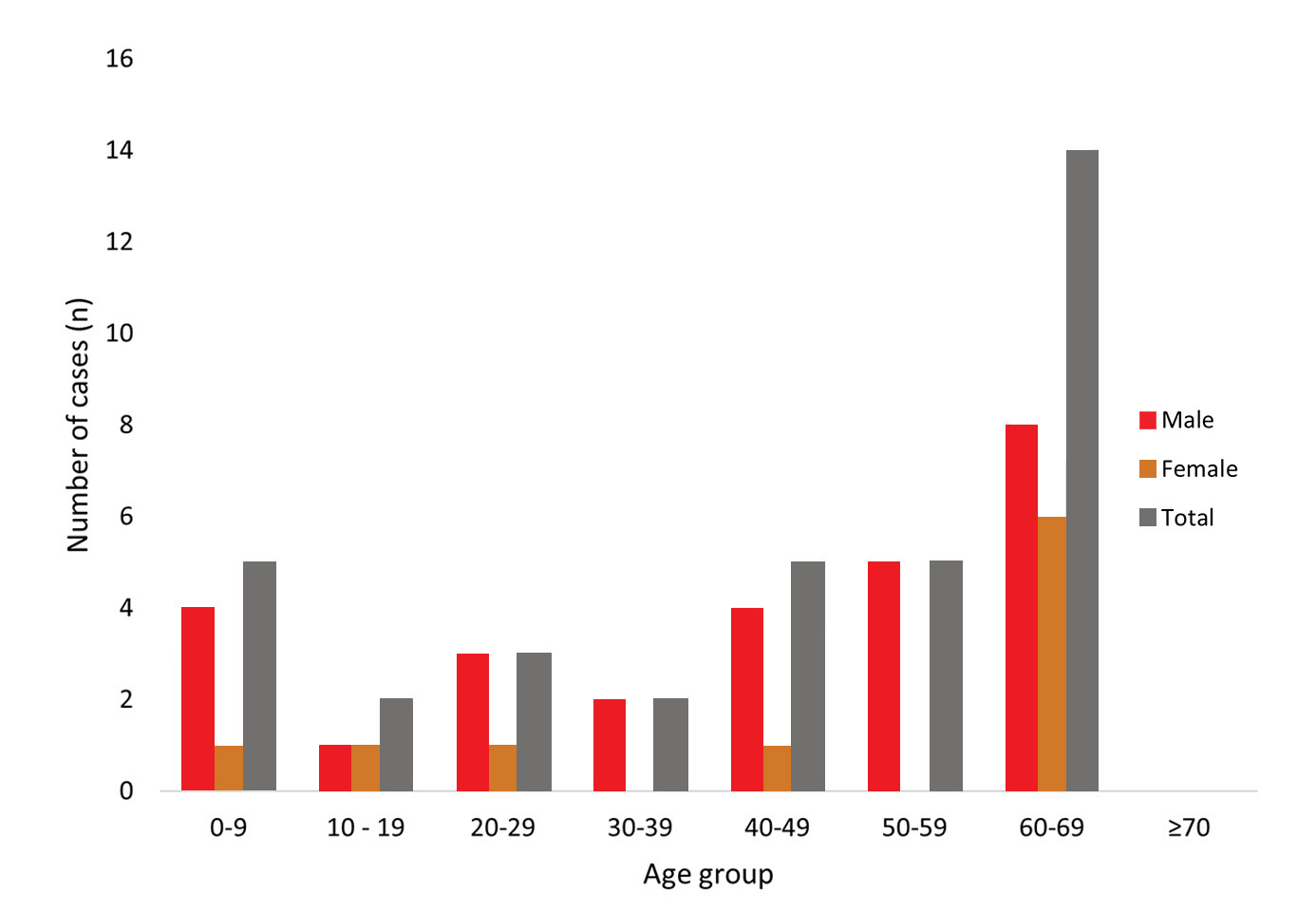

Figure 2: Age and Gender Distribution TBE case numbers 2004-2023

NOTE: The TBE case definition is different from the E-CDC definition.

| Age groups (years) | Males | Females | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-9 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| 10-19 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 20-29 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 30-39 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 40-49 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| 50-59 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| 60-69 | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| >70 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

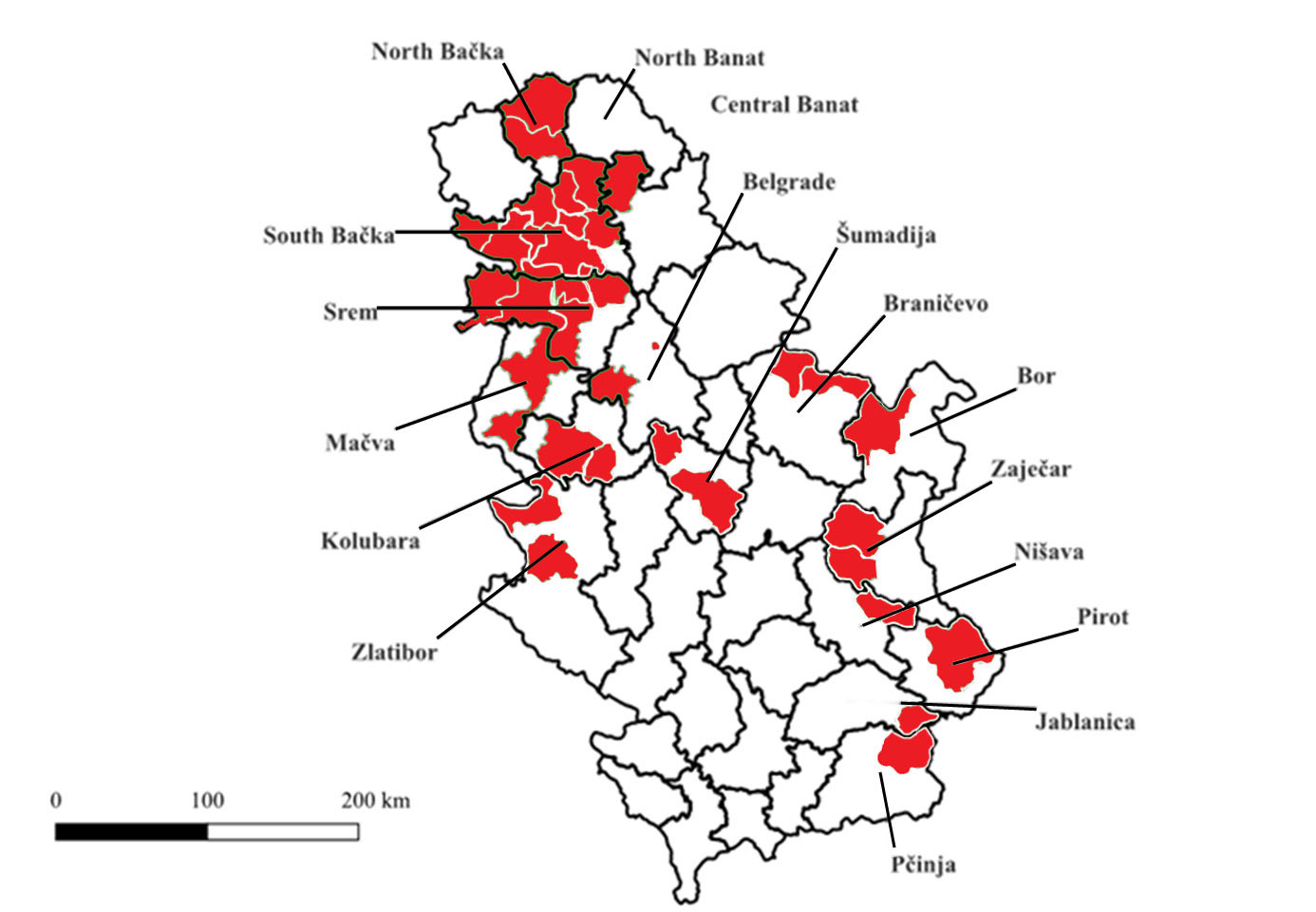

Figure 3: Map of Serbia where red marks municipalities where tick infestation occurred for each person tested for TBEV-neutralizing antibodies in the most recent serosurvey8. Persons with TBEV-neutralising antibodies were exposed to tick bites in the regions of Šumadija (Mountain Bukulja), Srem (Mountain Fruška Gora) and Mačva (Mountain Divčibare).

Acknowledgments

TBE epidemiology data for the period 2004-2018 was provided by Institute of Public Health of Serbia “Dr. Milan Jovanović Batut” and Institute of Public Health of Vojvodina

Contact

Pavle Banović

Pavle.banovic@mf.uns.ac.rs

Author

Citation

Banović P, TBE in Serbia. Chapter 13. In: Dobler G, Erber W, Bröker M, Chitimia-Dobler L, Schmitt HJ, eds. The TBE Book. 7th ed. Singapore: Global Health Press; 2024. doi:10.33442/26613980_13-28-7

References

- Bordoski M, Gligić A, Bosković R. Arbovirus infections in Serbia. Vojnosanit Pregl. 1972;29(4):173-175.

- Vesenjak-Hirjan J, Punda-Polić V, Dobe M. Geographical distribution of arboviruses in Yugoslavia. J Hyg Epidemiol Microbiol Immunol. 1991;35(2):129-140.

- Potkonjak A, Petrović T, Ristanović E, et al. Molecular Detection and Serological Evidence of Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus in Serbia. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 2017;17(12):813-820. doi:10.1089/vbz.2017.2167

- Holzmann H. Diagnosis of tick-borne encephalitis. Vaccine. 2003;21 Suppl 1:S36-40.

- Popović Dragonjić L, Vrbić M, Tasić A, et al. Fatal Case of Imported Tick-Borne Encephalitis in South Serbia. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2022;7(12):434. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed7120434

- Kunze M, Banović P, Bogovič P, et al. Recommendations to Improve Tick-Borne Encephalitis Surveillance and Vaccine Uptake in Europe. Microorganisms. 2022;10(7):1283. doi:10.3390/microorganisms10071283

- Jakimovski D, Mateska S, Dimitrova E, et al. Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus and Borrelia burgdorferi Seroprevalence in Balkan Tick-Infested Individuals: A Two-Centre Study. Pathogens. 2023;12(7):922. doi:10.3390/pathogens12070922

- Banović P, Mijatović D, Bogdan I, et al. Evidence of tick-borne encephalitis virus neutralizing antibodies in Serbian individuals exposed to tick bites. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1314538. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1314538

- Jovanović V. Report on Infectious Diseases in the Republic of Serbia for the Year 2022. Institute of Public Health of Serbia “Dr. Milan Jovanović Batut”; 2023. Accessed 24 March, 2024. https://www.batut.org.rs/download/izvestaji/GodisnjiIzvestajZarazneBolestiSrbija2022.pdf

- Pustahija T. Seroprevalence and epidemiological characteristics of tick-borne encephalitis in Vojvodina. University of Novi Sad; 2023. Accessed 24 March, 2024. https://nardus.mpn.gov.rs/bitstream/handle/123456789/21781/Disertacija_14132.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Poluga J, Barac A, Katanic N, et al. Tick-borne encephalitis in Serbia: A case series. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2019;13(06):510-515. doi:10.3855/jidc.11516

- Lončarević G. Stručno-metodološko uputstvo za sprovođenje obavezne i preporučene imunizacije stanovništva za 2017. Accessed 24 March, 2024. https://www.batut.org.rs/download/SMUzaRedovnuImunizaciju2017.pdf