Tserennorov Damdindorj, Uyanga Baasandagva, Uranshagai Narankhuu, Tsogbadrakh Nyamdorj, Burmaajav Badrakh and Burmaa Khoroljav

E-CDC risk status: endemic

(data as of end 2022)

History and current situation

In Mongolia, TBEV was first isolated (Kraminskii V.A) from marmot liver in Dornod province in 1979, while the Ixodes persulcatus tick was identified in 1987 by M. Dash.1,2 I. persulcatus is a taiga tick distributed in coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruces and larches.3 Much of northern Mongolia is covered in coniferous forest, and the southern edge of the Siberian taiga is located along the Khangai and Khentii mountains.

Since the 1980s, Mongolian scientists worked together with researchers from the Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology of Irkutsk, Russia to investigate the spread of ticks carrying the TBEV in the forest areas of Khuvsgul, Khentii, Bulgan, Selenge, Orkhon, Central, Dornod, Arkhangai and Uvurkhangai provinces, which had been identified as TBEV-endemic regions.4 Finally in 1989, following available local information on diseases suspected to be TBE, Abmed et al. documented natural foci of the TBEV in the administrative districts of Zelter, Bugant and Khuder in the Selenge province and noted that it is important to plan and implement preventive measures.5

A family physician in the city of Khuder in the province of Selenge remembers that she had treated more than 400 patients with clinical signs of tick-borne infections from 1993–2000. Five of them had died and had been recorded as “viral infections“. This is the first evidence to indicate that TBE was prevalent at that time.6

The Selenge province was found to carry the highest counts of I. persulcatus ticks frequently infected with the TBEV. I. persulcatus ticks were also found to be abundant in the Bulgan, Tuv, Khuvsgul and Orkhon provinces of Mongolia.1,7,10 Human cases of TBE have been officially registered at the national level since 2005.

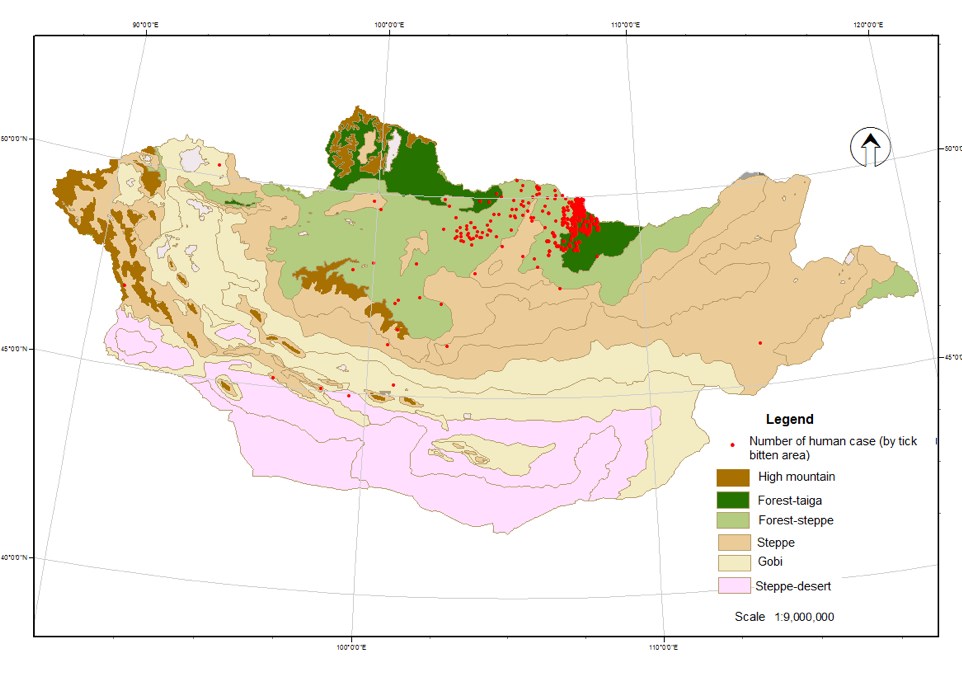

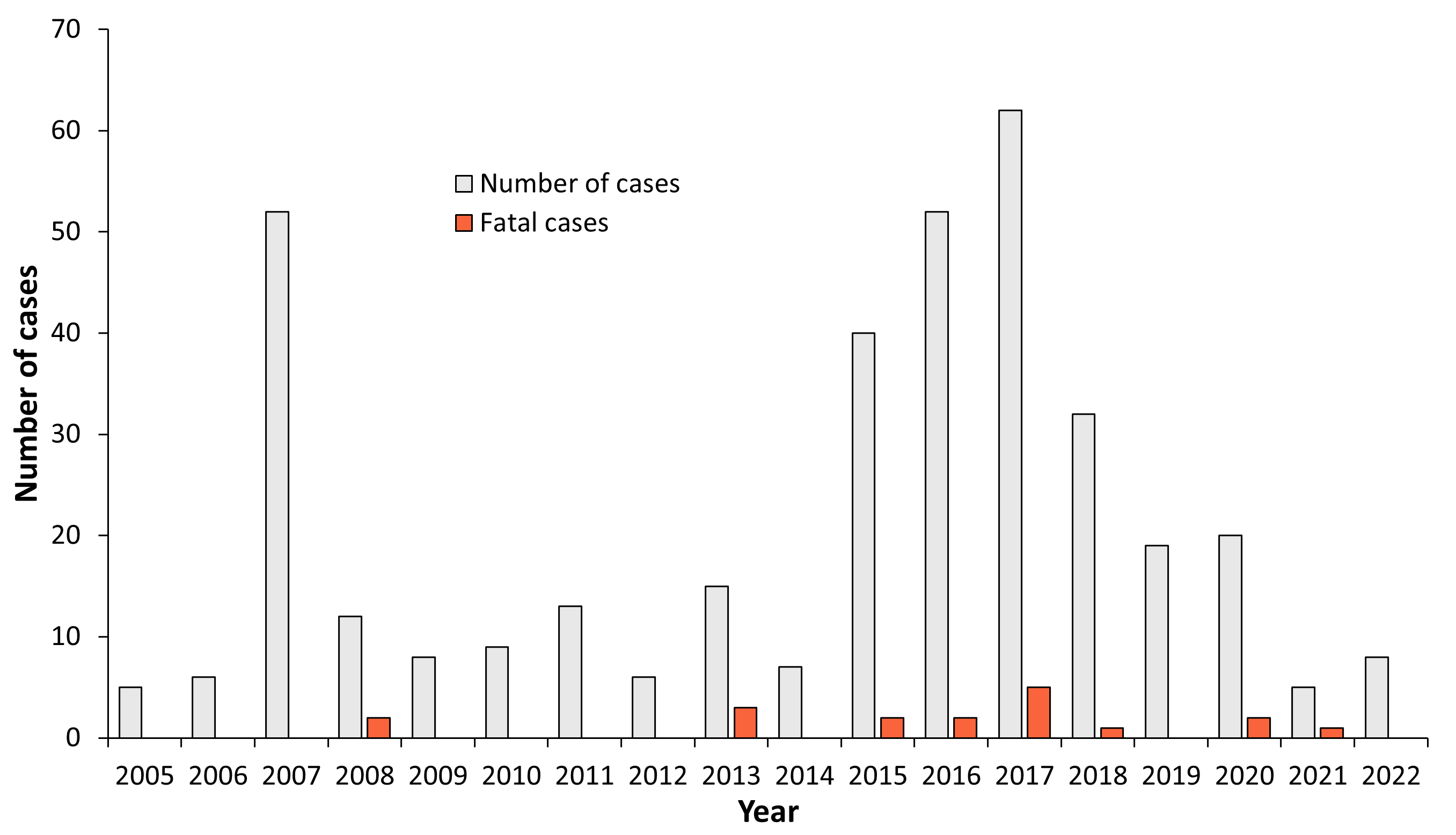

Between 2005–2022, 371 confirmed cases have been registered in Arkhangai, Bayankhongor, Bulgan, Darkhan-Uul, Dundgobi, Dornod, Orkhon, Uvurkhangai, Selenge, Tuv, Uvs, Khunsgul, Khentii provinces and Ulaanbaatar city. Most patients remembered a tick bite had occurred in the area of the Selenge (78%) and Bulgan (12%) provinces. During this period (2005–2022), there were 18 fatal cases (CFR 4.85%) attributed to severe meningoencephalitis (Fig. 1).

Since 2005, prevention measures such as vaccination, training and advocation among the population have been administered but human cases continue to be registered. Between 2014 and 2017, TBE cases and deaths increased annually, but declined in the last five years (2018–2022). TBE cases have also been recorded from areas without the main vector I. persulcatus. Moreover an expansion of natural TBEV-foci has been observed.8-12

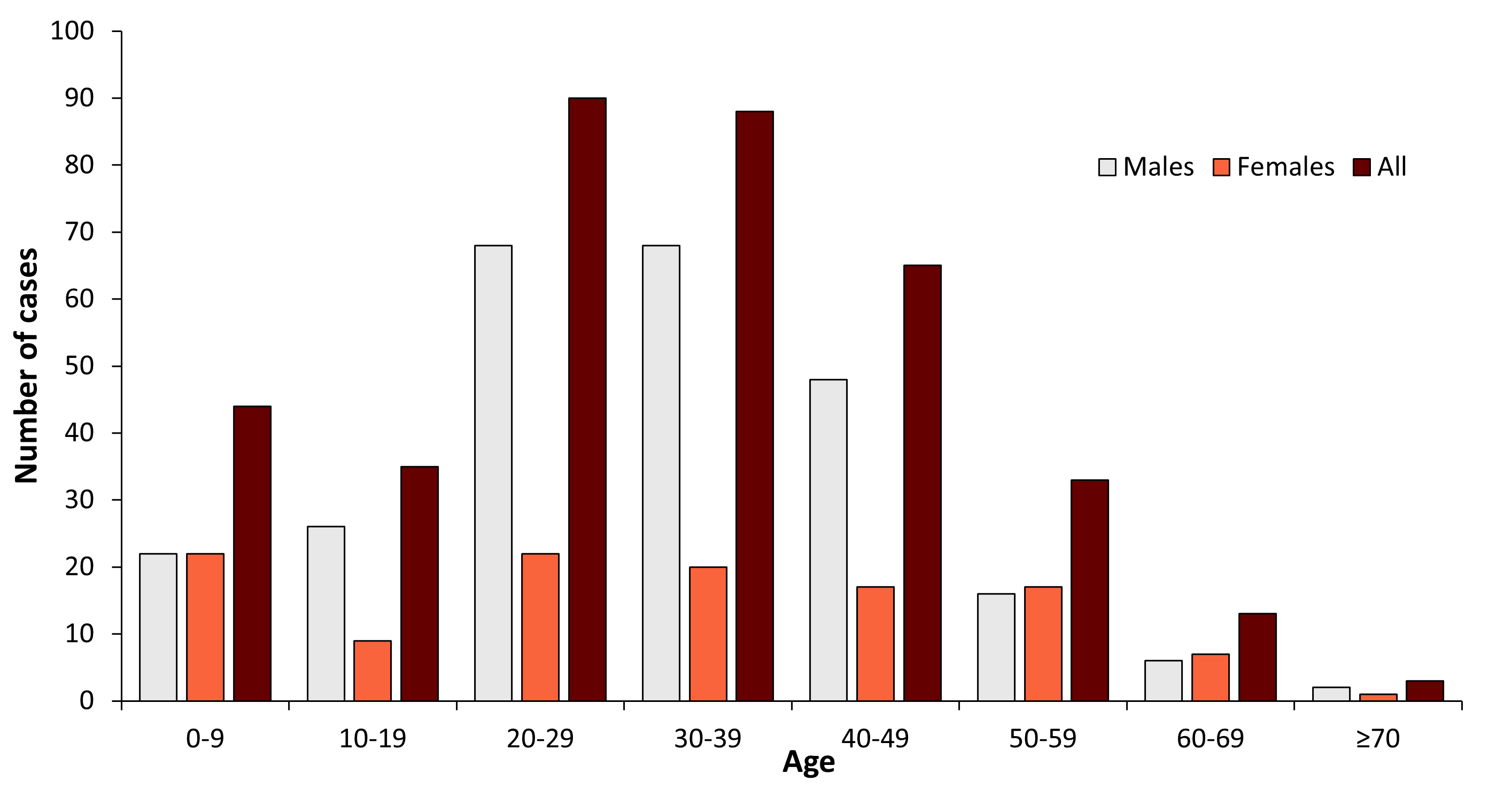

Most infections occurred among Individuals between 20–49 years of age, and it was 2.7–4.5 times higher than other age groups. Also, men more frequently contracted the disease (2.3, p<0.001) than women (Fig. 2). The majority of subjects were bitten by ticks when they had been collecting plants and picnicking during May and June.7

According to a survey of long-term neurological symptoms in 37 TBE-recovered individuals in Selenge province, 5 (16.1%) of them manifested with fever, 6 (19.4%) with paralysis, 8 (25.8%) with meningoencephalitis and 12 (38.7%) with meningitis when they were ill. After recovery between one to twelve years, 78.4% of them had headache, 30%–40% of them had fatigue, forgetfulness, decreased ability to concentrate and stiff neck, 10%–20% had hearing loss, paralysis, and a small percentage (3.2%) of them still had mental change, shoulder muscle atrophy, back muscle tone and muscle tremors convulsions.24

Vaccination against TBE has been consistently carried out since 2005 in the risk areas of the country.13-15 A molecular biological study of TBEV was performed in collaboration with researchers from Germany and Russia and determined the prevalent viral subtypes by genetic sequencing.7,15-20,22

Overview of TBE in Mongolia

| Table 1: Virus, vector, transmission of TBE in Mongolia | |

|---|---|

| Viral subtypes, distribution8,16-21 |

|

| Reservoir animals | Not documented |

| Infected tick species (%)7-8 | I. persulcatus (3.18±2.5%) D. silvarum (2.9±2.6%) D. nuttalli (0.6%) |

| Dairy product transmission | Not reported |

| Table 2: TBE-reporting and vaccine prevention in Mongolia | |

|---|---|

| Mandatory TBE reporting | Patients with clinical suspected TBE are reported to the National Center for Zoonotic Diseases (NCZD) where the diagnosis can be microbiologically confirmed (anti-TBEV-IgG and IgM by ELISA). Any patient with serologically confirmed TBE or by PCR is reported to the Center for Health Development and also to the Ministry of Health, Mongolia. (Source: http://hdc.gov.mn/) |

| Other TBE-surveillance | National Center for Zoonotic Diseases and its local branches (15 Centers for zoonotic diseases in provinces) are conducting TBE surveillance in ticks and in the population of endemic areas.4,6,9-11 |

| Special clinical features | Clinically, 37.7% of patients have fever only, 34.6% suffer from meningitis, 26.5% from meningoencephalitis and 1.2% from encephalomyelitis. By age, fever dominates in age groups 0–9 and 40–49 years, meningitis in the age groups of 10–39 and 50–59 years and meningoencephalitis in those >60 years.7,11,12 In terms of age and sex, 20–49 year olds (65.6%) and males (69.3%) are the most affected groups. Among all affected males, those aged 10–49 years (81.8%) comprised the majority of male cases.7,8 The overall CFR was 4.85% between 2005 and 2022 with an annual range between 3.1%–20%. |

| Available vaccines | Russian vaccine – EnceVir and TBE-Moscow. |

| Vaccination recommendations and reimbursement | Persons in a risk population of most endemic provinces can receive TBE vaccination free of personal charge. Vaccination is also recommended for anybody living in or visiting known endemic areas with a risk for tick bites. (Source: The Order A160 on 21 April 2017 approved by the Minister of Health Annex 4: Guidelines for prevention and control of tick-borne diseases) |

| Vaccine uptake by age group/ risk group/ general population | TBE vaccination is organized since 2005. As of 2017, 51,000 persons from 13 provinces and the capital have been vaccinated, i.e., 2.1% of the total population. Vaccine uptake in endemic provinces ranges between 0.2%–23%.12-15 |

| Name, address/website of TBE National Reference Center | National Center for Zoonotic Diseases, Songinokhairkhan dictrict, 20 khoroo, Ulaanbaatar, 18131, Mongolia Source: (www.nczd.gov.mn) |

Figure 1: TBE cases and mortality, 2005–2022

| Year | Number of Cases | Fatal cases | Incidence / 105 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 5 | 0 | 0.21 |

| 2006 | 6 | 0 | 0.23 |

| 2007 | 52 | 0 | 2.06 |

| 2008 | 12 | 2 | 0.47 |

| 2009 | 8 | 0 | 0.3 |

| 2010 | 9 | 0 | 0.33 |

| 2011 | 13 | 0 | 0.46 |

| 2012 | 6 | 0 | 0.21 |

| 2013 | 15 | 3 | 0.5 |

| 2014 | 7 | 0 | 0.23 |

| 2015 | 40 | 2 | 1.33 |

| 2016 | 52 | 2 | 1.8 |

| 2017 | 62 | 5 | 2.0 |

| 2018 | 32 | 1 | 0.97 |

| 2019 | 19 | 0 | 0.57 |

| 2020 | 20 | 2 | 0.60 |

| 2021 | 5 | 1 | 0.15 |

| 2022 | 8 | 0 | 0.23 |

Figure 2: Age and gender distribution of TBE in Mongolia (2005–2022, n=371)

| Age group (years) | Males | Females | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-9 | 22 | 22 | 44 |

| 10-19 | 26 | 9 | 35 |

| 20-29 | 68 | 22 | 90 |

| 30-39 | 68 | 20 | 88 |

| 40-49 | 48 | 17 | 65 |

| 50-59 | 16 | 17 | 33 |

| 60-69 | 6 | 7 | 13 |

| ≥70 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 256 | 115 | 371 |

Table 3: TBEV-isolation and TBE cases in Mongolia

| Year of isolation | Strain name | Source of isolation | Location of isolation |

| 200419 | Siberian | I. persulcatus | Selenge province |

| 200816 | Far-Eastern | Patient brain | Bulgan province |

| 201015 | Siberian | I. persulcatus | Bulgan province |

| 201217 | Siberian | I. persulcatus | Selenge province |

| 201317 | Siberian | I. persulcatus | Selenge province |

| 201420 | Siberian | I. persulcatus | Selenge province |

| 202022 | Far-Eastern | Patient brain | Bulgan province |

57% of TBE cases (incidence 9.51/100,000) occurred in the forest-taiga range, 40% (incidence 0.56/100,000) in the forest-steppe range, 0.7% (incidence 0.12/100,000) in steppe range, and 2.8% (incidence 0.1–0.27/100,000) in other ranges, including steppe-desert, Gobi and high mountain (Fig. 3).

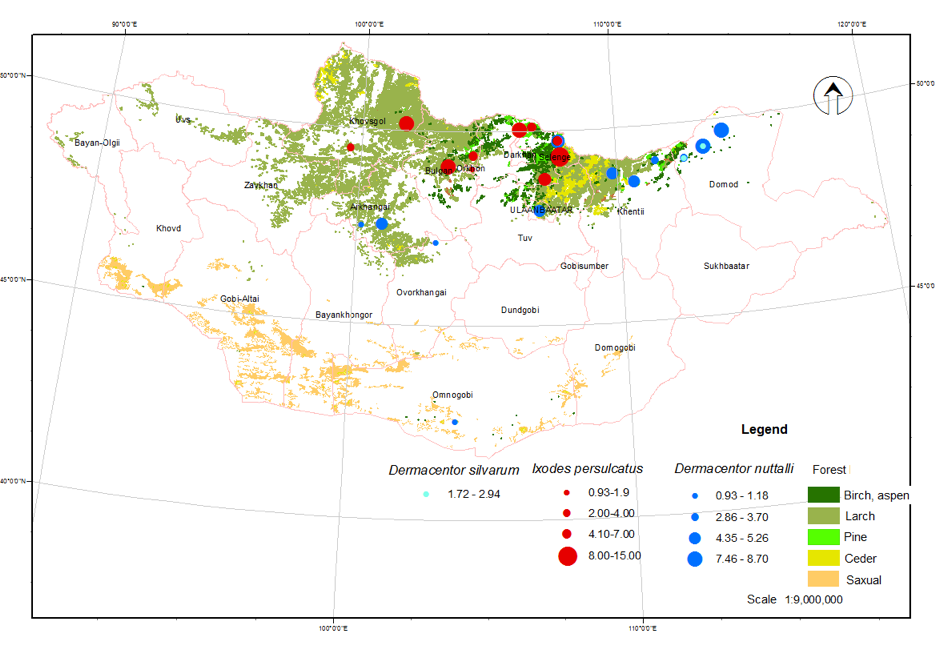

According to surveillance efforts since 2006, 10,464 ticks have been collected. Following species identification, 14.7% (1,540) were classified as Ixodes persulcatus, 79.3% (8,300) were Dermacentor nutalli, 3.2% (341) were Dermacentor silvarum, and 2.8% (283) were Hyalomma asiaticum.8

I. persulcatus ticks were collected from 13 districts of Selenge, Bulgan, Orkhon, Darkhan-Uul, Khentii and Khuvsgul provinces. Most cases were found in Selenge (66%) and Bulgan (23%) provinces. The total tick infection rate was 3.18±2.5% and the highest infection rates were found in the Bugat district of Bulgan Province (7.5%) and in the Mandal district (6.3%) and Khuder district (3.75%) of Selenge province.

D. nuttalli ticks were collected from 43 districts of 12 provinces and Ulaanbaatar city. The total tick infection rate for the entire country was 0.61% with the highest infection rates (3.3%–7.8%) in Khentii, Selenge, Arkhangai and Dornod province.

D. silvarum ticks were collected from Dornod and Khentii provinces and the tick infection rate was 2.9±2.6% (Fig. 4).

Contact:

Citation:

Tserennorov D, Uyanga B, Uranshagai N, Tsogbadrakh N, Burmaajav B, Burmaa K. TBE in Mongolia. Chapter 12b. In: Dobler G, Erber W, Bröker M, Schmitt HJ, eds. The TBE Book. 6th ed. Singapore: Global Health Press;2023. doi:10.33442/26613980_12b22-6

References

- Bataa J, Abmed D. Tick-borne diseases Handbook. Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. 2007:20-25.

- Dash M, Bуambaa B, Trasevich IV. Handbook of New rickettsial diseases. Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia: Ma: Esun Erdene press; 1994:9.

- Wikipedia contributors. Ixodes persulcatus. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. April 10, 2021, at 21:59 UTC. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ixodes_persulcatus. Accessed June 1, 2016.

- Abmed D, Bataa J, Tserennorov N, et al. Natural foci of transmissible tick-borne infections in northern and central Mongolia. Actual aspects of natural focal diseases ”Materials of the interregional scientific-practical conference, Omsk. 2001:23.

- Abmed D, Ganbold D, Andreev VN, Lvov S, Dmitriev DB. The study of tick-borne encephalitis in Selenge aimag (province). The Center for Research of infectious diseases with natural foci, research book. 1990;(6):67-69.

- Veteran doctor D. Renchenkhand’s memoirs. Mong J Infect Dis Res. 2018;3(80):74-75

- Uyanga B. Epidemiological characteristics and prevalence of tick-borne encephalitis in Mongolia 2005-2017. Dissertation. 2019.

- Uyanga B, Burmaajav B, Tserennorov D, et al. Geographical distribution of Tick-borne encephalitis and its vector in Mongolia, 2005-2016. Cent Asian J Med Sci. 2017;3(3):250-8.

- Uyanga B, Tserennorov D, Badrakh B, Damdin O, Baatar U, Tsogbadrakh N. The increasing importance species of the species of Dermacentor.spp tick in tick-borne encephalitis of Mongolia. 16th Medical Biodefense Conference Munich, 28—31 October, 2018 organized by Bundeswehr Institute of Microbiology ABSTRACTS –P. 111

- Uyanga B, Burmaajav B, Tserennorov D, Undra B. Epidemiological features of tick-borne encephalitis registered in Mongolia, 2005-2016. Mongolian Journal of infectious disease research. 2017;5(76):36-41.

- Uyanga B, Tserennnorov D, Purevdulam L, Tsogbadrakh N. Tick-borne encephalitis in Mongolia.Mong J of Infect Dis Res. 2015;5(64):13-34

- Tserennorov D, Uyanga B, Battsetseg J, Bayar C, Baigalmaa B, Njamsuren M. Results of a study of tick-borne encephalitis and analysis of human cases in Mongolia. Far Eastern Journal of Infectious Pathology (Medical Scientific Review Journal). 2014;25:36-9.

- Uyanga B, Unursaikhan U, Undraa B, Tsogtsaikhan S, Davaalkham D. Epidemiological characteristics of tick-borne encephalitis and vaccination results. J Infect Pathol. 2012;19(3):114.

- Uyanga B, Adiyasuren Z, Tsogtsaikhan S, Davaalkham D. Results of tick-borne encephalitis vaccination. J Mong Med Sci. 2010;3(153):64-70.

- Bataa J, Abmed D, Tsend N, et al. Results of immunization against tick-borne encephalitis in Mongolia. Biotechnical research, production and use. 2004:20-24.

- Frey S, Mossbrugger I, Altantuul D, et al. Isolation, preliminary characterization, and full-genome analyses of tick-borne encephalitis virus from Mongolia. Virus Genes. 2012;45(3):413-25.

- Khasnatinov MA, Danchinova GA, Kulakova NV, et al. Genetic characteristics of the causative agent of tick-borne encephalitis in Mongolia. Vopr Virusol. 2010;55(3):27-32.

- Tserennorov D, Höper D, Binder K, et al. Epidemiological and Molecular Biological Characterization of TBEV in Mongolia; 15th Medical Biodefence Conference, Munich, Germany. 2016:30-31

- Tserennorov D, Uyanga B, et al. Study of Tick-borne Encephalitis Virus in Mongolia. Biodefence conference; 14th Medical Biodefence conference, Munich, Germany. 2013:29-30

- Abmed D, Khasnatinov M, J.Bataa J, et al. Molecular, epidemiological, ecological study of tick-borne encephalitis virus in Mongolia, Mong J Infect Dis Res, Ulaanbaatar. 2005;4(7):22-5.

- Erdenechimeg D, Boldbaatar B, Enhmandakh Y, Myagmarsukh Y, Oyunnomin N, Purevtseren B. Identification of the Siberian type of the tick-borne encephalitis virus and serological surveillance in Mongolia. Mong J Agric Sci. 2014;13(2):19-26

- Walder G, Lkhamsuren E, Shagdar A, et al. Serological evidence for tick-borne encephalitis, borreliosis, and human granulocytic anaplasmosis in Mongolia. Int J Med Microbiol. 2006;296 Suppl 40:69-75.

- Uyanga B, Burmaajav B, Natsagdorj B, et al. A case series of fatal meningoencephalitis in Mongolia: epidemiological and molecular characteristics of tick-borne encephalitis virus. Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal. 2019;10(1):1-7. doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2018.9.1.003

- Uyanga B, Oyun B, Oyunchimeg S, et al. Long-term neurological outcome of tick-borne encephalitis in Mongolia. Mong J Infect Dis Res. 2021;4(99):78/28